Shamanic Deities in Korean Buddhism

Buddhism is not an exclusivistic religion. It has tended to accommodate to the native forms of religion in whatever country it has spread, and that holds true for Korea as well. Indeed, in Korea there is no clear boundary between Buddhism and Shamanism. Certainly, we can see a distinct difference between the “professionals”, Buddhist monks and Mudangs have distinct identities and clearly demarcated institutional roles in society. However, the distinction between Buddhist and Shamanist “believers” is anything but clear. As a matter of fact, most Koreans who participate in Shamanist practices identify themselves primarily as Buddhists, and there is no perceived contradiction between the two. Buddhist entities (Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, famous monks of the past) are included among many the personal deities of many Mudangs, and Buddhist temples often contain shrines for native shamanic deities. The two most commonly found shamanic deities enshrined within Buddhist temple precincts are Sanshin (the Mountain Spirit) and Chilseong (the Seven-Stars Spirit), and somewhat less common are Dokseong (the so-called “Lonely Saint”) and Yongwang (the Dragon King).

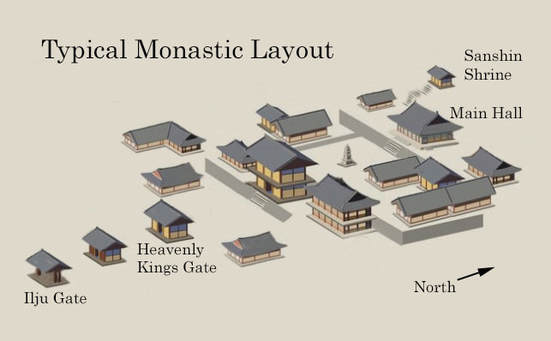

The shrines for these shamanic deities can be of various form, but certain characteristics are generally consistent. According to the principles of fengshui (風水, 풍수 Pungsu in Korean), Buddhist temples are laid out on a north-south axis facing south, with a progressive movement from “lower” to “higher”. The temple visitor enters the sacred precincts through the southern-most gate (一株門, 일주문 Ilju-mun), proceeds up the path through the Gate of the Four Guardian Kings (天王門, 천왕문 Cheonwang-mun), then passes beneath the two-story Lecture Pavilion (樓閣, 누각 Nugak) which functions as the gateway to the upper terrace, and finally faces the Main Buddha Hall (大雄殿, 대웅전 Daeungjeon), the most lofty position in the temple complex. All these structures are aligned on the main north-south axis, with other buildings and compounds along either side. The shamanic shrines, however, are always to the east or west OFF the central axis and BEYOND the Main Buddha Hall, thus symbolically being situated at the margin of the formal Buddhist institutional precincts, where the ordered spiritual realm merges into the “wild” realm of the mountain.

Here is an example of a typical monastic layout in Korea, showing the placement of the shaman shrine to the northwest of the Main Hall:

Here is an example of a typical monastic layout in Korea, showing the placement of the shaman shrine to the northwest of the Main Hall:

The common term for shamanic spirit paintings is Mushindo (무신도), and these are normally distinguished from the more formal and elaborate Buddhist-style temple paintings (Taenghwa 탱화). The same shamanic spirits may be depicted in both Mushindo and Taenghwa, but their appearance can be quite different. Mushindo may be considered folk paintings, often done by the Mudang herself, and are usually quite simple, even naive in style, while Taenghwa (whether shamanic or purely Buddhist) are professionally painted with elaborate details and careful adherence to formal iconographic features. The examples we are discussing here of shamanic deities enshrined within Buddhist temple precincts are without exception of the Taenghwa type.

The most commonly found shrine is that of Sanshin, the Mountain Spirit. The Sanshin Shrine (山神閣 산신각 Sanshin-gak) may be a tiny structure too small for a person to enter, housing a painting of the Mountain Spirit, a couple of candles and an incense burner, but in most cases it is large enough for several people to enter, with cushions on the floor for seating. There will always be a large painting of Sanshin and a simple altar on the north side of the shrine, but occasionally there may be a statue of Sanshin and his tiger on the altar as well. Sanshin is always portrayed in a natural mountain setting, usually as an old man with long wispy white beard (but occasionally in female form) accompanied by his tiger, and sometimes even seated on the tiger. The tiger can be seen as the embodiment of the wild untamed spirit of the mountains, and may also be seen as the “alter ego” of Sanshin himself. Historically tigers were well known in Korea, and they roamed the mountains throughout the peninsula until the early 1900s. They were hunted to extinction by the Japanese during the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), and the last Siberian tiger in Korea was killed in 1922. (See the 2015 South Korean film 대호 “The Tiger: An Old Hunter’s Tale”). In Korea folk belief, tigers were seen as fierce and powerful, even fearful, but never malevolent, and in folk paintings they are often depicted along with a pair of magpies as protective symbols of good luck and prosperity. [image] So as the Mountain Spirit, Sanshin’s identification with the tiger is quite natural.

The second most commonly found shamanic deity in Buddhist temples is Chilseong (七星, 칠성), the Seven Stars Spirit, identified with the constellation Ursa Major (the Big Dipper), and his shrine is called Chilseong-gak (칠성각, 七星閣). This shamanic deity is unique in several ways. First, Chilseong is usually portrayed as seven separate figures, even though he is normally thought of as a single spirit. Furthermore, Chilseong can be portrayed as seven Confucian-style court officials, or as seven standing Buddha figures, often with an additional central seated Buddha flanked by the Bodhisattvas of the Sun and the Moon (Ilgwang Bosal 일광보살 and Wolgwang Bosal 월광보살 ). Here we can see the clearest example of assimilation between shamanism and Buddhism in Korea. The images of Chilseong in Buddhist temples are usually painted by professional artists, and are often quite elaborate with detailed and precise Buddhist iconography. However, the folk paintings of Chilseong that are used by Mudangs, kept in their personal shrines, are simpler and less explicitly Buddhist in nature, and sometimes even portray Chilseong (as well as Sanshin) in female form, something that would not normally be found within a Buddhist monastic complex.

The third shamanic deity sometimes found in Buddhist temples is Dokseong (독성, 獨聖), the so-called “Lonely Saint”, also called Naban Jonja (나반존자, 那畔尊者). Sometimes Dokseong will have his own shrine (Dokseong-gak, 독성각, 獨聖閣), but more commonly he will be included as one of a trinity of spirits (along with Sanshin and Chilseong) enshrined in the Three Saints Hall (Samseong-gak, 삼성각, 三聖閣). This deity has a somewhat ambiguous background, often being identified with some particular famous Buddhist monk of the past, sometimes identified as one of the Buddha’s disciples, but at other times he is thought of as a Daoist hermit. In any case, Dokseong is clearly included within the Korean shamanic pantheon, and is only marginally associated with Buddhism. Interestingly, it is his iconographic depiction that gives him his Buddhist or Daoist association. He is depicted as an old man with shaved head, white eyebrows and no beard (but sometimes with facial stubble), dressed in monk’s robes and usually holding a Buddhist rosary (염주, yeomju), seated on the ground in a semi-meditation pose, often with one knee raised. He will sometimes be depicted with exceedingly long eyebrows.

There is one more shamanic deity sometimes found within the precincts of a Buddhist monastery. This is Yongwang, the Dragon King (용왕 龍王). The Asian dragon is a benevolent power, whose realm is the sea, rivers, and the monsoon storm clouds (in contrast to the malevolent nature of the traditional Western dragon which inhabits caves, breathes fire, hoards treasure and devours maidens). As the ruler of life-giving waters, the Dragon King is often found enshrined near a mountain spring within the precincts of a Buddhist temple, and in purely shamanic contexts Yongwang is sometimes portrayed in female form as well. Yongwang is normally depicted as an elderly male figure with white beard, courtly robes and a crown. The two main characteristics that distinguish images of Yongwang are the presence of dragons and billowing waves. Another unique feature often found in paintings of Yongwang is a distinctive spiky beard and eyebrows, something seldom seen in other shamanic deities.